Originally a white suburb on the far eastern edge of the District of Columbia, just over the Anacostia River from the main part of the city, Kenilworth was subdivided in the late 1890's. Named for the famous Kenilworth Castle in England and for Sir Walter Scott's novel of romance and courtly intrigue set there, houses slowly went up where once there were only farms and open fields. W.B. Shaw started his famous water gardens there (now the Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens) around 1900, which attracted thousands of visitors to the area, including presidents and foreign dignitaries. The suburb became a quiet and closely-knit neighborhood. It was connected to the rest of the city by Kenilworth Avenue, which led to Benning Road and Benning's Bridge, and by a trolley line which ended at the DC-Maryland border.

Houses also began appearing on Douglas Street, the street that led to W.B. Shaw's gardens, about the same time that Kenilworth was subdivided. Adjacent to Kenilworth but not technically a part of the subdivision, it was a street where African American families could quietly build small houses and have a relatively peaceful community life during a time when the nation was still sorting out the racial upheaval from the Civil War.

In the 1940's, the U.S. government put up temporary housing for white war workers on empty land close to Shaw's lily ponds, which had become a national park. By the time those were torn down in the 1950's, white flight had come to Kenilworth. Deanwood, just across the railroad tracks, had always been a black neighborhood. Eastland Gardens, just to the south of Kenilworth, had begun in the late 1930's as a community of young, middle class black families and was rapidly expanding. The highway had also come through and, in the widening of Kenilworth Avenue, the church and many of the homes and stores that had been the nucleus of the neighborhood were torn down. Most of the white Kenilworth families not displaced by the highway chose to move out; many relocated in Prince George's County, the new 'suburbs.'

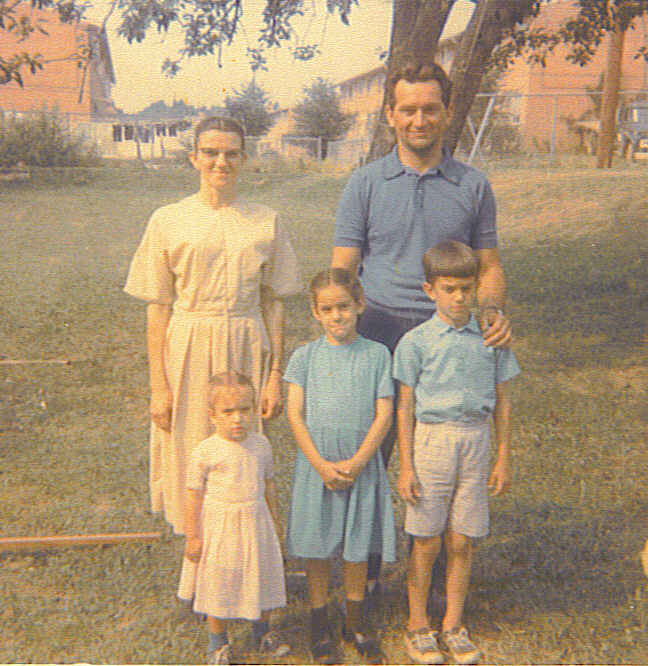

In 1959, Kenilworth Courts opened, one of the new wave of government sponsored low income housing complexes popping up around the city. When my parents, Elmer and Fannie Lapp, moved to Douglas Street in 1965, they moved into a neighborhood that, except for themselves, was almost one hundred percent African American. They sent their children to the local public school and began to get to know their neighbors.

Soon other workers came, and neighborhood children flocked to the Sunday School programs, Bible and craft classes, and playground activities that the church sponsored. In 1975, a church house was built at 4459 Douglas Street. The church is still there, still racially mixed, and still active in the neighborhood.

In the 1970's and 1980's, Kenilworth Courts was on the leading edge of a national tenant management movement. Spearheaded by a dynamic former welfare mom named Kimi Gray and helped along by political leaders such as Jack Kemp and Mayor Marion Barry, the Kenilworth reform movement turned into a tenant management corporation. As residents began to manage the complex, rent collection rates went up, public works services improved, and many residents tapped into educational programs and found jobs. The complex was extensively renovated in the late eighties and early nineties.

Though the early promise of the resident management movement has dimmed somewhat, Kenilworth still has many proud residents who remember when they 'did it themselves' and turned their neighborhood around. They still work together, sometimes against tall odds, to make their community a safe and peaceful place to live.

And though my parents moved out of the neighborhood and back to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania in 2001, the community still remembers them as the first of many Mennonites who came to their streets to live along side them and bring the message of God's love to Kenilworth and Douglas Street.

Photo credit (boy diving): Washington Post 8/12/83 photo, by Dudley M. Brooks

Keep in touch - Joe (lappjoe@yahoo.com)